A couple of weeks ago I attended the Lift France 2011 conference. For me this was different than my usual conference experience. I have written before how Anglo-Saxon my perspective is, so to be at a conference where the majority of the audience is French was refreshing.

Although there was a track about learning, most of the conference approached the effects of digital technology on society from angles that were relatively new to me. In a pure learning conference, I am usually able to contextualize what I see immediately and do some real time reflecting. This time I had to stick to reporting on what I saw (all my #lift11 posts are listed here) and was forced to take a few days and reflect on what I had seen.

Below, in random order, an overview of what I would consider to be the big themes of the conference. Occasionally I will try to speculate on what these themes might mean for learning and for innovation.

Utilization of excess capacity empowered by collaborative platforms

Robin Chase gave the clearest explanation of this theme that many speakers kept referring back to:

This world has large amounts of excess capacity that isn’t used. In the past, the transaction costs of sharing (or renting out) this capacity was too high to make it worthwhile. The Internet has facilitated the creation of collaborative platforms that lower these transaction costs and make trust explicit. Chase’s most simple example is the couch surfing idea and her Zipcar and Buzzcar businesses are examples of this too.

Entangled with the idea of sharing capacity is the idea of access being more important than ownership. This will likely come with a change in the models for consumption: from owning a product to consuming a service. The importance of access shows why it is important to pay attention to the (legal) battles being fought on patents, copyrights, trademarks and licenses.

I had some good discussions with colleagues about this topic. Many facilities, like desks in offices, are underused and it would be good to try and find ways of getting the percentage of utilization up. One problem we saw is how to deal with peak demand. Rick Marriner made the valid suggestion that transparency about the demand (e.g. knowing how many cars are booked in the near future) will actually feed back into the demand and thus flatten the peaks.

A quick question that any (part of an) organization should ask itself is which assets and resources have excess capacity because in the past transaction costs for sharing them across the organization were too high. Would it now be possible to create platforms that allow the use of this extra capacity?

Another question to which I currently do not have an answer is whether we can translate this story to cognitive capacity. Do we have excess cognitive capacity and would there be a way of sharing this? Shirky’s Cognitive Surplus and the Wikipedia project seem to suggest we do. Can organizations capture this value?

Disintermediation

The idea of the Internet getting rid of intermediaries is very much related to the point above. Intermediaries were a big part of the transaction costs and they are disappearing everywhere. Travel agents are the canonical example, but at the conference, Paul Wicks talked about PatientsLikeMe, a site that partially tries to disintermediate doctors out of the patient-medicine relationship.

What candidates for disintermediation exist in learning? Is the Learning Management System the intermediary or the disintermediator? I think the former. What about the learning function itself? In the last years I have seen a shift where the learning function is moving away from designing learning programs into becoming a curator of content and service providers and a manager of logistics. These are exactly the type of activities that are not needed anymore in the networked world. Is this why the learning profession is in crisis? I certainly think so.

The primacy (and urgency) of design

Maybe it was the fact that the conference was full of French designeurs (with the characteristic Philippe Starck-ish eccentricities that I enjoy so much), but it really did put the urgency of design to the forefront once again for me. I would argue that design means you think about the effects that you would like to have in this world. As a creator it is your responsibility to think deeply and holistically. I will not say that you can always know the results of your design (product, service, building, city, organization, etc.), there will be externalities, but it is important that you leave nothing to chance (accident) or to convenience (laziness).

There is a wealth of productivity to be gained here. I am bombarded by bad (non-)design every single day. Large corporations are the worst offenders. The only design parameter that seems to be relevant for processes is whether they reduce risk enough, not whether they are usable for somebody trying to get something done. Most templates focus on completeness and not on aesthetics or ease of use. When last did you receive a PowerPoint deck that wasn’t full of superfluous elements that the author couldn’t be bothered to remove?

Ivo Wenzler reminded me of Checkhov’s gun (no unnecessary elements in a story). What percentage of the learning events that you have attended in the last couple of years adhered to this?

We can’t afford not to design. The company I work for is full of brilliant engineers. Where are the brilliant designers?

Distributed, federated and networked systems

Robin Chase used the image below and explicitly said that we now finally realize that distributed networks are the right model to overcome the problems of centralized and decentralized systems.

I have to admit that the distinction between decentralized and distributed eludes me for now (I guess I should read Baran’s paper), but I did notice at Fosdem earlier this year that the open source world is urgently trying to create alternatives to big centralized services like Twitter and Facebook. Moglen talked about the Freedombox as a small local computer that would do all the tasks that the cloud would normally do, there is StatusNet, unhosted and even talk of distributed redundant file systems and wireless mesh networking.

Can large organizations learn from this? I always see a tension between the need for central governance, standardization and uniformity on the one hand and the local and specific requirements on the other hand. More and more systems are now designed to allow for central governance and the advantages of interoperability and integration, while at the same time providing configurability away from the center. Call it organized customization or maybe even federation. I truly believe you should think deeply about this whenever you are implementing (or designing!) large scale information systems.

Blurring the distinction between the real and the virtual worlds

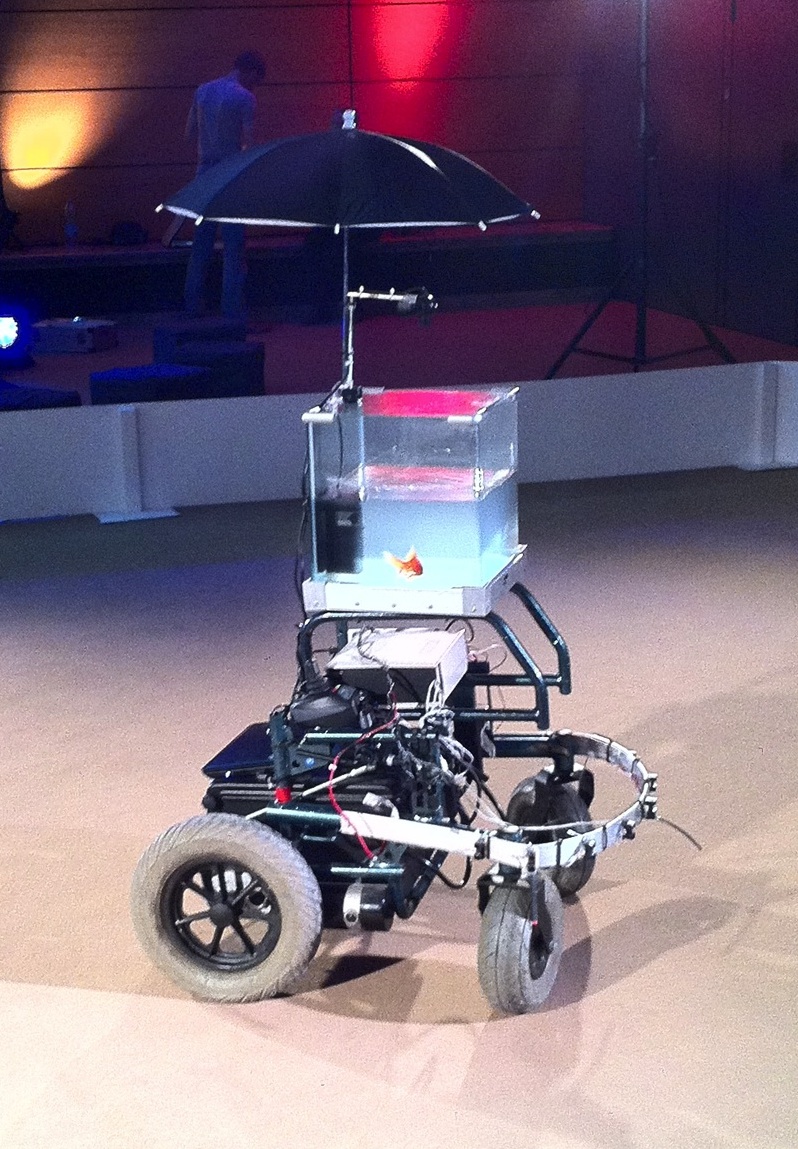

Lift also had an exhibitors section titled “the lift experience“, mostly a place for multimedia art (imagine a goldfish in a bowl sat atop an electric wheelchair, a camera captured the direction the fish swam in and the wheelchair would then move in the same direction). There were quite a few projects using the Arduino and even more that used “hacked” Kinects to enable new types of interaction languages.

Most projects tried, in some way, to negotiate a new way of working between the virtual and the real (or should I call it the visceral). As soon as those boundaries disappear designers will have an increased ability to shape reality. One of the projects that I engaged with the most was the UrbanMusicalGame: a set of gyroscopes and accelerometers hidden in soft balls. By playing with these balls you could make beautiful music while using an iPhone app to change the settings (unfortunately the algorithms were not yet optimized for my juggling). This type of project is the vanguard of what we will see in the near term.

Discomfort with the dehumanizing aspects of technology

A surprising theme for me was the well articulated discomfort with the dehumanizing aspects of some of the emerging digital technologies. As Benkler says: technology creates feasibility spaces for social practice and not all practices that are becoming feasible now have positive societal impact.

One artist, Emmanuel Germond, seemed to be very much in touch with these feeling. His project, Exposition au Danger Psychologique, made fun of people’s inability to deal with all this information and provided some coy solutions. Alex Peng talked about contemplative computing, Chris de Decker showed examples of low-tech solutions from the past that can help solve our current problems and projects in the Lift Experience showed things like analog wooden interfaces for manipulating digital music.

This leads me to believe that both physical reality and being disconnected will come at a premium in the near future. People will be willing to pay for having real experiences versus the ubiquitous virtual experiences. Not being connected to the virtual world will become more expensive as it becomes more difficult. Imagine a retreat which markets itself as having no wifi and a giving you a free physical newspaper in the morning (places like this are starting to pop up, see this unplugged conference or this reporter’s unconnected weekend).

There will be consequences for Learning and HR at large. For the last couple of years we have been moving more and more of our learning interventions into the virtual space. Companies have set up virtual universities with virtual classrooms, thousands and thousands of hours of e-learning are produced every year and the virtual worlds that are used in serious games are getting more like reality every month.

Thinking about the premium of reality it is then only logical that allowing your staff to connect with each other in the real world and collaborate in face to face meetings will be a differentiator for acquiring and retaining talent.

Big data for innovation

I’ve done a lot of thinking about big data this year (see for example these learning analytics posts) and this was a tangential topic at the conference. The clearest example came from a carpool site which can use it’s data about future reservation to clearly predict how busy traffic will be on a particular day. PatientsLikeMe is of course another example of a company that uses data as a valuable asset.

Supercrunchers is full of examples of data-driven solutions to business problems. The ease of capturing data, combined with the increase in computing power and data storage has made doing randomized trials and regression analysis feasible where before it was impossible.

This means that the following question is now relevant for any business: How can we use the data that we capture to make our products, services and processes better? Any answers?

The need to overcome the open/closed dichotomy

In my circles, I usually only encounter people who believe that most things should be open. Geoff Mulgan spoke of ways to synthesize the open/closed dichotomy. I am not completely sure how he foresees doing this, but I do know that both sides have a lot to learn from each other.

Disruptive software innovations currently don’t seem to happen int the open source world, but open source does manage to innovate when it comes to their own processes. They manage to scale projects to thousands of participants, have figured out ways of pragmatically dealing with issues of intellectual property (in a way that doesn’t inhibit development) and have created their own tool sets to make them successful at working in dispersed teams (Git being my favorite example).

When we want to change the way we do innovation in a networked world, then we shouldn’t look at the open source world for the content of innovation or the thought leadership, instead we should look at their process.

Your thoughts

A lot of the above is still very immature and incoherent thinking. I would therefore love to have a dialog with anybody who could help me deepen my thoughts on these topics.

Finally, to give a quick flavour of all my other posts about Lift 11, the following word cloud based on those posts: