Amber Case is a founder of Geoloqi and a cyborg anthropologist. Some of the themes that interest her are “ambient intimacy”, “the automatic production of space” (you can put stuff in your computer, but it doesn’t get heavier), “the digital dark age”, “persistent paleontology”, “information jetlag”, her dislike for skeuomorphs and “cellphones as providing temporarily negotiated private space”. According to her we are all cyborgs now. The minute you look at a screen you are in a symbiotic relationship with technology. Most of the tools from the beginning of time were an extension of our physical selves. Right now we are starting to see tools emerging that are extensions of our mental selves. From a fixed interface, we have now moved to liquid interfaces on our screens which can be infinitely configured. What will be the next step in the interface world?

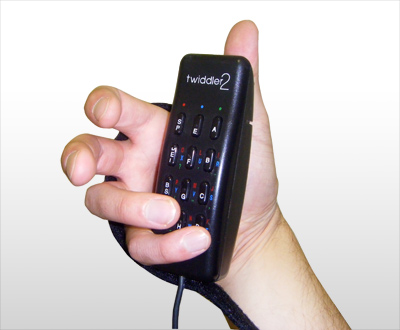

Steve Mann already wore a computer in 1981. He was the first person to lifestream his life. He wrote a great paper titled WearCam, the wearable camera. He worked on the concept of diminished reality where he would cancel out the ads and brands that he didn’t like. One of his issues was how do you type? So the Twiddler,a one-handed USB keyboard, came out. He could get about 90 words a minute with it. He created contextual notification systems for “remember the milk” type of things. He built in face recognition software. He went from 80 pounds of gear in the early 80s to the current situation where he has the information laser projected onto his eye.

“Calm technology” was research done at Xerox Parc in the 70s. It is exactly what it says that it is: actions become buttons, there are invisible interfaces and there are trigger-based actions. The haptic compass belt is a great example of calm technology. At Geoloqi they realised that with geo-technology you can now make invisible buttons. So for example your lights will turn on when you enter your geo-fenced house. This will allow your phone to become a remote control for reality. She showed a lot of examples of what you can do with geofencing. One example was mapattack.org.

The conclusion of her talk: The best technology is invisible, gets out of your way and helps you connect to people.